Last Updated on June 3, 2023

A surge in hanging deaths among middle-aged adults appears to result in the notable increase in U.S. suicides between 2000 and 2010, a new study finds.

Hangings accounted for 26 percent of suicides in 2010, up from 19 percent in the beginning of the decade. Among those aged 45 to 59, suicide by hanging improved 104 percent in that period of time, in accordance with the report documenting shifting suicide patterns.

Overall, 16 percent more Americans took their very own lives than in 2000. That is equivalent to 12.1 suicides per 100,000 people compared to 10.4 per 100,000 previously.

“It’s essential that the huge increase in suicide by hanging be comprehended,” said lead researcher Susan Baker, founding director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Injury Research and Policy in the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore.

Greater education and public knowledge about death by hanging are needed to help come this specific approach, she and other pros said and the suicide rate overall.

“People may believe death by hanging is instantaneous and painless, but folks fight . . . I’m sure it’s not painless by any means,” Baker said.

For the study, published in the December issue of the American Journal of Preventive Medicine, Baker’s team used data in the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

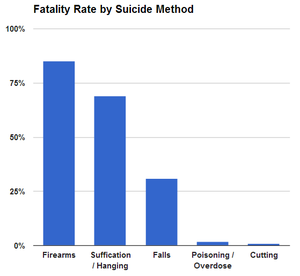

Guns remain the main strategy of suicide. Guns, poisoning and hanging account for 93 percent of suicides in the U.S., Baker’s group found. Although suicide by firearms dropped nearly one quarter among 15- to 24-year-olds, it climbed by nearly exactly the same sum among those aged 45 to 59.

Suicide by poisoning grown to 17 percent of all suicides, up from 16 percent in 2000. Self-inflicted death by poisoning increased most (85 percent) among people aged 60 to 69 years, the investigators found.

Other tendencies the researchers noted:

- Suicide rates are increasing among women than men, and faster among whites than in non-whites.

- In terms of age, the suicide rate rose the most (39 percent) among people 45 to 59, while falling 8 percent among those 70 and elderly.

A current newspaper in exactly the same journal reported that more people die by suicide in the United States than in car crashes, making suicide the top source of injury deaths.

A report published Nov. 5 in The Lancet said about 1,500 more suicides have occurred since 2007 than anticipated, and it credited about one-quarter of the suicide increase to the sagging economy.

Baker said restricting access to firearms and narcotic painkillers has helped reduce suicides calling for those procedures, and she wants to see for hanging similar strategies adopted to limit opportunities.

For example, building codes can make sure that pipes and overhead light fixtures are unable to support the weight of a person, she said.

And clothes bars in cupboards should be got when excess weight is placed on them to break away, Baker said.

Nonetheless, restricting access to hanging is a lot more difficult than restricting access to poisons or firearms, experts said.

“These new findings pose a serious challenge for injury prevention efforts due to the widespread access to rope and other means for hanging,” said Simon Rego, director of psychology training at Montefiore Medical Center in New York City.

Lanny Berman, executive director of the American Association of Suicidology, agreed.

“This shift will demand advanced attempts by those in the suicide prevention community and by policy makers to effectively reach the desired targets of the revised National Strategy for Suicide Prevention,” Berman said.

That program was recently infused to finance suicide prevention plans. The goal is to save 20,000 lives in the next five years.

With all the exception of the United States, hanging has been the number one method of suicide in high-income nations world-wide, Berman said.