Last Updated on June 22, 2023

New research Indicates combining mindfulness meditation and running into a mental health plan could help reduce depression.

While studies have found that exercise and Meditation can affect mental health, a study published last month at Translational Psychiatry unites both.

“Scientists have known for some time that the two of these activities alone can help with depression,” states Tracey Shors, a professor of exercise science at Rutgers and co-author of the analysis. “But This study indicates that when done collectively, there’s a striking improvement in depressive symptoms together with gains in synchronized brain activity.”

Fifty-two people took part in the study. The volunteers did 30 minutes of exercise and meditated for thirty minutes, for eight months. The researchers studied their ability to predispose and concentrate before and after.

Twenty-two participants with depression reported a reduction in symptoms. The people in the study without a diagnosis of depression reported a reduction in anxiety, thoughts and improvement.

Lead author of the study, Brandon Alderman, hypothesises that the mechanisms could be strengthened.

From author Gretchen Reynolds in The New York Times:

“We know from animal studies that effortful learning, such as is involved in learning how to meditate, encourages new neurons to grow” in the hippocampus, [Alderman] said.

So while the practice probably increased the amount of new brain cells in each volunteer’s hippocampus, Dr. Alderman said, the meditation might have helped to keep more of these neurons alive and working than if people hadn’t meditated.

It remains to be seen whether these improvements last, as this is a small study.

The brain could be changed by running in ways that are beneficial to health, according to a fascinating study of a treatment programme for people with depression.

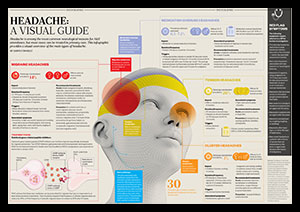

As many people know from experience, depression is partly characterised by an inability to stop dwelling on unhappy memories and thoughts. Researchers suspect that this pattern of thinking, called rumination, involves two areas of the brain in particular: the prefrontal cortex, a region of the brain that helps control focus and attention, and the hippocampus, which is important for learning and memory. Some studies have found that people with depression have a smaller hippocampus.

Interestingly, exercise and meditation do affect these parts of the mind. For example, people who meditate show different patterns of communication in their prefrontal cortex during tests. These differences are thought to indicate that meditators have a heightened ability to focus and concentrate.

Meanwhile, animal studies show that exercise increases the production of new brain cells in the hippocampus.

Both exercise and meditation have also been shown to be beneficial.

These various findings about meditation and exercise intrigued researchers at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, N.J., who began to wonder if, since exercise and meditation on their own improve mood, combining the two might intensify the effects of each.

Therefore, for the new study, which was published last month in Translational Psychiatry, the researchers recruited women and 52 men, 22 of whom had been diagnosed with depression. The researchers asked all the volunteers to complete an assessment of their ability to concentrate while detectors measured signals and then confirmed the identification.

The researchers found that the volunteers showed signalling patterns in their prefrontal cortex related to attention and concentration.

The researchers had the volunteers all start a programme of sitting.

To begin with, the volunteers were taught a type of meditation known as attention. Essentially mindfulness meditation, it requires people to sit and think by counting their breaths backwards to 10. It’s not an easy practice.

“If people found their minds wandering” during meditation, especially if they started to ruminate on unpleasant memories, they were told not to worry or judge themselves, “but simply to start counting back from one,” said Brandon Alderman, a professor of exercise science at Rutgers who led the study.

The volunteers meditated in this way for 20 minutes, then did a 10-minute meditation in which they stood and paid attention.

They then got on treadmills or stationary bikes in the lab and jogged or pedalled at a moderate pace for 30 minutes (with a five-minute warm-up and five-minute cool-down).

The volunteers completed these sessions once a week. The researchers analysed their performance and mood.

There were significant changes. The 22 volunteers with depression had a 40% reduction in symptoms of the problem. In particular, they reported a tendency to ruminate on memories.

Meanwhile, those in the control group reported feeling happier than at the start of the study.

Objectively, the effects on the volunteers’ brain activity and ability tests were different. The team with depression showed brain cell activity in their prefrontal cortex that was identical to that of people with depression. They sharpened their focus, which is thought to help reduce rumination and improve concentration.

“I was very surprised that we saw such a strong effect after only eight months,” said Dr Alderman.

He and his colleagues theorise that the exercise and meditation may have had an effect on the volunteers’ brains.

“We know from animal studies that effortful learning, such as that involved in learning to meditate, stimulates the growth of new neurons in the hippocampus,” he said.

So while the exercise most likely increased the amount of new brain cells in each volunteer’s hippocampus, Dr Alderman said, the meditation may have helped keep more of those neurons alive and working than if people hadn’t meditated.

Since some studies suggest that being mindful of your breathing and your body increases people’s enjoyment of their effort, meditation may also have made exercise more tolerable, he said.

“I started meditating,” said Dr Alderman, a long-time athlete.

This was a The scientists and the study didn’t follow their volunteers, so whether any mood improvements lasted, they don’t know. They also have no idea whether similar or greater benefits might happen if someone were to practice both tasks or meditate and then run on alternating days. They intend to investigate these questions in experiments.